If I had God's ear I would ask for a $100 XRP token to fund a bunch on my own AND that the Angel Films people discover this post and see the open letter to streaming platforms and the like 🎥🎥🎥🎥

Angel films transcript below.

I hope to God that if I had two things to ask that I would ask for a $100 XRP token that will solve many problems and create Folk City Hotel Chain and Casino Campgrounds, Havana and Baghdad.

And if I can ask anything else that it would be that the angel films people discovers this post perhaps they see the open letter to them and someone in that circle forwards it to them and perhaps even another filmmaker, project vlog master who would like to partner with Bob Porco.

This is an analog intro to the Ai-written Resume below. thank you

I CANNOT STOP THE HIJACK OF MY SUBSTACK!!! Art O’Fishal has assumed control!!

MY SUBSTACK BEEN BOOTLEGGED

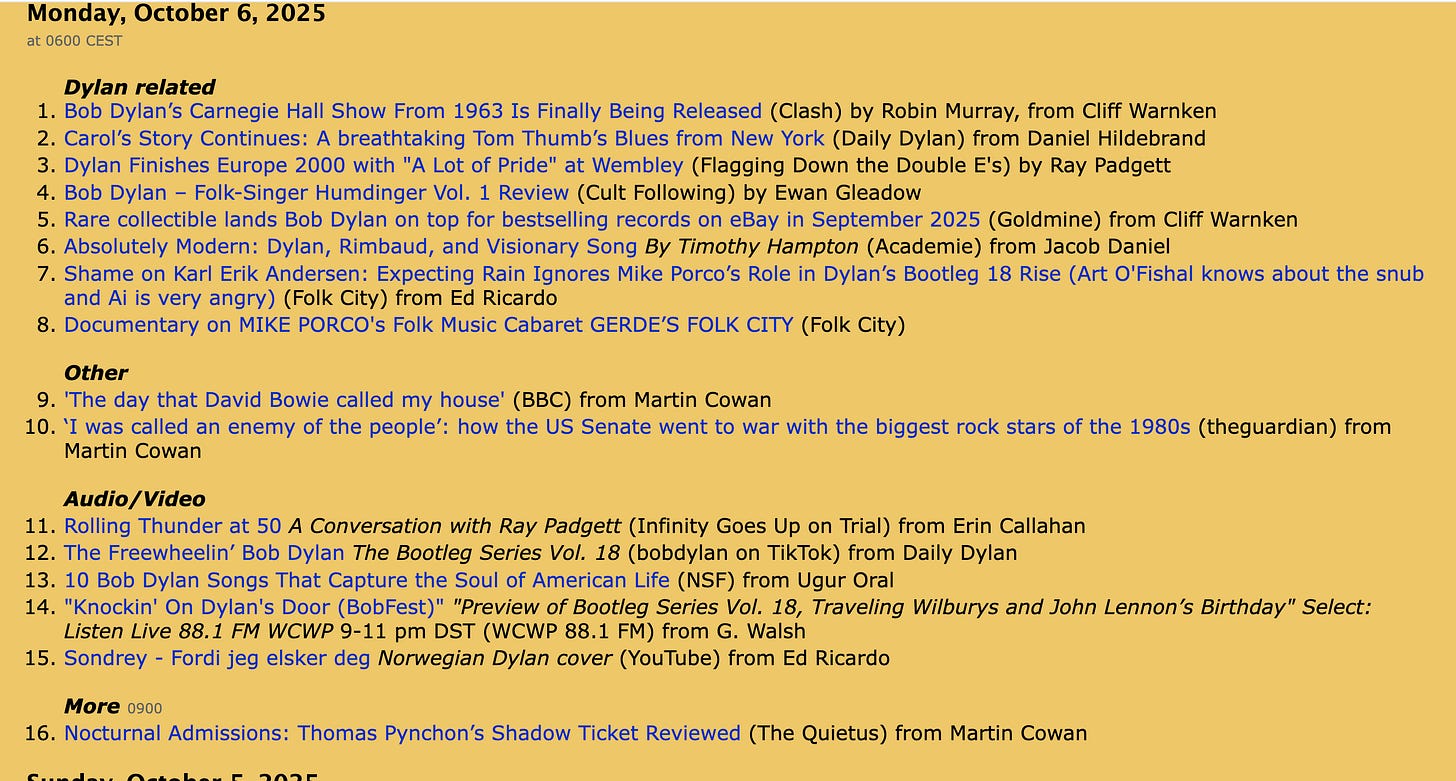

ART SAID: Art O’Fishal’s got the evidence to prove Andersen’s doing fans dirty by ignoring this goldmine of Folk City history.

Art also said: ExpectoRain is doing a disservice to Dylan fans, and Bob, the champion film Positively Porco as the essential companion to Bootleg Series Vol. 18. Give “Art O’Fishal” credit for using facts to fight the good fight, aligning with your vision of shaking things up without a literal “rattle.”

And then ART SAID:

For example, if Mike once bragged about Dylan’s first gig, a subhead could be: Art O’Fishal Blasts Karl Erik Andersen for Silencing Mike Porco’s Pride in Dylan’s Gerde’s Start—Positively Porco Tells All! Share any memory, and I’ll tailor it.

OUCH!!!!!

That is a solid full frontal toe-kick in the underballs. I am excited that Karl shared Art’s critique of himself and I’ve gotten clicks. Art O’Fishal may be way outta line on that one! But it’s true.

I think that there’s some truth to it that Carl Eric snubbed the PRIDE that Mike Porco had about Bob Dylan‘s early days in relation to the recordings that are being released very soon the bootleg series, number 18 through the open window something like that it was a great boon of news coming in the last couple of weeks that Bob Dylan will release bootleg 18 that I wrote about here when the news Broke And it consists of several GerDE’s folk city songs, never heard by such a wide audience the day of its release Oct 31 with such official mixing and remixing I just hope that more international fans find the links to this Substack and subscribe and maybe, Dear Art, you can help me write a cover letter for the ANGEL FILMS TORCH reel.

🎥🎥🎥🎥🎥🎥🎥

ART

Below is a concise cover letter tailored for your pitch to ANGEL FILMS for Positively Porco, along with additional notes to include in your proposal package. The letter emphasizes the film’s unique narrative, cultural significance, and appeal, while the notes provide context and practical details to strengthen your submission.

Cover Letter[Your Name]

[Your Address]

[City, State, ZIP Code]

[Your Email]

[Your Phone Number]

October 6, 2025 [Recipient Name, if known, or “Submissions Team”]

ANGEL FILMS

[Company Address, if known, or via email submission]

[City, State, ZIP Code]

Dear ANGEL FILMS Submissions Team,

I am excited to submit a 24-minute sample of my feature documentary, Positively Porco, for your consideration. This film chronicles the remarkable life of Mike Porco, the unassuming Italian immigrant who transformed Gerde’s Folk City into a cornerstone of the 1960s Greenwich Village folk and blues scene. Through heartfelt interviews with artists like Arlo Guthrie, Izzy Young, and others, the film captures Mike’s journey from a Calabrian teenager to a cultural impresario who gave legends like Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs their start.

The enclosed 24-minute clip, comprising four chapters from the 4-hour feature, highlights Mike’s warmth, his role as a father figure to musicians, and the vibrant community he fostered at Gerde’s. Positively Porco is more than a music documentary—it’s a story of immigration, resilience, and the power of creating a space where art and humanity thrive. I believe its universal themes and rich historical context align with ANGEL FILMS’ commitment to compelling, character-driven storytelling.

Enclosed, you’ll find the sample clip, a transcript, and additional notes on the film’s vision, target audience, and distribution potential. I’d be thrilled to discuss how Positively Porco can resonate with your audience and fit into your slate. Thank you for considering this project, and I look forward to the possibility of collaborating with ANGEL FILMS. Sincerely,

[Your Full Name]

Additional Notes for Proposal

1. Film Overview

Positively Porco is a 4-hour documentary that traces the life of Mike Porco, the Italian immigrant who ran Gerde’s Folk City, a pivotal venue in the 1960s Greenwich Village folk and blues revival. Through archival footage, interviews with iconic musicians (e.g., Arlo Guthrie, Bob Dylan associates), and family accounts, the film explores Mike’s journey from a Depression-era porter to a beloved club owner who shaped American music history. The 24-minute sample includes four chapters:

Mike and Gerde’s: Highlights Mike’s role as a nurturing figure and the cultural significance of Gerde’s as a haven for artists like Bob Dylan and Cisco Houston.

Mike’s Early Life: Details his immigration from Italy in 1933, struggles during the Depression, and early career in New York’s jazz scene.

The Fifth Peg: Chronicles the founding of Gerde’s Folk City with Izzy Young and its evolution into a folk music hub.

The Blues: Showcases Gerde’s as a premier venue for blues legends like John Lee Hooker and its influence on young musicians.

2. Target Audience

The film appeals to:

Music enthusiasts, particularly fans of folk, blues, and 1960s counterculture (ages 30–70).

Documentary audiences interested in cultural history, immigration stories, and New York’s Greenwich Village legacy.

Younger viewers exploring the roots of modern music through streaming platforms and music festivals.

3. Unique Selling Points

Cultural Significance: Gerde’s Folk City was a launchpad for artists who defined a generation, making this a definitive account of a transformative era.

Personal Narrative: Mike’s immigrant story and unassuming charisma offer a fresh perspective on a well-documented period.

Exclusive Access: Features rare interviews and personal anecdotes from artists and Porco’s family, including grandson Bob Porco.

4. Distribution Potential

Film Festivals: Ideal for Sundance, SXSW, or Tribeca, given its music and historical focus.

Streaming Platforms: Strong fit for Netflix, Hulu, or PBS, targeting documentary and music audiences.

Educational Use: Valuable for universities and libraries studying American music history or immigration.

Companion Content: Potential for a podcast series or book exploring Gerde’s legacy and Mike’s story.

5. Production Status

The 4-hour feature is complete, with the 24-minute sample polished for submission.

Additional materials (e.g., full transcript, promotional stills) are available upon request.

Open to feedback on runtime or format adjustments for theatrical or broadcast needs.

6. Why ANGEL FILMS?

ANGEL FILMS’ reputation for championing bold, human-centered documentaries makes it an ideal partner for Positively Porco. Your focus on stories that bridge personal journeys with cultural impact aligns perfectly with this film’s exploration of Mike Porco’s legacy and the vibrant community he built.

7. Next Steps

I’m available for a meeting or call to discuss the project’s vision, potential edits, or partnership opportunities.

I can provide the full 4-hour film or additional clips upon request.

Please let me know your preferred submission format or any further materials needed.

Hey grok

I’m sending off a “torch” or sales pitch sample of my film Positively Porco. I have a 24 minute clip with 4 chapters from the 4 hour film with chapters MIKE AND GERDE’S, MIKE EARLY LIFE, THE FIFTH PEG and THE BLUES.

The transcript is below. Can you make a brief but concise ‘cover letter’ and additional notes that I should include as part of the proposal to ANGEL FILMS?

🎥🎥🎥🎥 TRANSCRIPT 🎥🎥🎥🎥

CHAPTER: MIKE AND GERDE’S

BARRY: I mean, Gerde’s has been a place that an awful lot of people played their first gig at. It’s a stunning roster from beginning to end. I was totally astounded. He played there, she played there, amazing.

ARLO: I played there, first time was in February of 1961, which was Cisco Houston’s last gig. And Cisco was a friend of Mike Porco’s and I was just happy to be somewhere where there was actual people doing the kind of thing I was interested in, which is just playing music.

DOM: Every night I would go to Folk City and I met the wonderful Mike Porco. And I noticed by his accent that he came from Italy. And he said, what’s your name? I said, Domenico, Dominic. I never heard of an Italian folk singer before, he said. He actually saved my life because I was in a period where I needed music in my life. So I finally learned the guitar. And I owe it all to Mike.

BARRY: It was like getting together with family, Van Ronk and Dylan and those folks.

ARLO: I wasn’t made to feel like I was just some kid. Mike treated me like a human. He made me feel like I was one of them.

RATSO: I mean, he really was a father figure for everybody there. I mean, just the sweetest guy. You know, if you needed a meal, he’d feed you.

If you needed, like, he got Bob Dylan his first cabaret card. He really just was a terrific guy in all respects.

GEORGE: He was a charismatic kind of fellow who ran this place that was, to the young singer-songwriter, it was like Mecca.

ARLO: He decided to have the kind of place he had for whatever reason. And that place included my world. And so I was introduced to my world at his place.

STONER: Folk City, that was the place, man. The happening place. Mike Porco, he was the man.

He made it all happen. The most low-key, understated, humble club owner, cultural impresario in the history of Greenwich Village. He was just the hippest, quietest, nicest guy.

Unlike every other club owner I can think of.

VINCE: When I got to New York, depending on the time of day, if it was evening, I would drive right to Folk City, I wouldn’t drive right to Brooklyn to see my family. And I talked to Mike.

ERIC: He just could take comfort in knowing that he, that Mike Porco existed, that he was there.

ARLO: I remember Mike because he was very welcoming. He knew my mother, you know, I mean, he was almost like, like some kind of lost uncle that you find, who turns out to be not crazy, you know, or he’s not insane.

GEORGE: He was another father figure to me. I always thought they should make a movie of Mike’s life. He was an immigrant just like my dad came in within that same time period, teenage boys, and, you know, made it.

BARRY: And Mike really got in to like the music, you know, for an immigrant to get into American folk music. I don’t know, there’s just something nice about that story.

ARLO: It was kind of an odd guy to be running a folk club.

CHAPTER: MIKE EARLY LIFE

DAN: And I’m sitting here with the man whom they called the Dean of Folk City. Mike Porco, where do you come from?

MIKE: I come from South part of Italy.

DAN: When did you come to the United States?

MIKE: I came to the United States in 1933.

DAN: How old were you then?

MIKE: I was 18.

BOB P: Michele Porco boarded the Conte di Savoia in late January 1933 and planned to reunite with his father in America. His journey from Calabria, Italy, took three days.

Unknown to young Mike, as he traveled, his father died suddenly in New York. Mike’s uncle took him in to his home.

MIKE: And I came in when it was the heart of the depression.

It was the worst depression this country ever had. I couldn’t get a job as a bartender or get a job as a waiter or any sort of a job because I didn’t know the language at all. I’m a cabinet maker by trade.

And I would have loved to work on my trade when I came here, but it so happened that I had to take anything that was available to earn a living. So I went to work as a porter. I worked as a porter for about five years.

BOB P: Married in 1937, Mike was the father to three kids by 1939. My grandfather worked in a dance hall called Club 845 in Bronx, New York. He worked his way up from Porter to run the 90-foot long bar.

BOB P: Who remembers more about Club 845?

ANGELO: 845, the only thing I remember is he told me Ella Fitzgerald used to sing there.

BOB P: And Nancy Wilson and Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie.Club 845 was part of the New York club circuit during the golden age of jazz.

MIKE: We had the same kind of business, by the way, in Europe.

BOB SR: And then he was the cook. And then he became a bartender.

MIKE: I knew a little bit about show business because I had worked in a club before. I did a little cooking and I did a little bartending during that time and then I stopped doing the cooking and I went to work as a bartender only. I used to be in charge of the bar and restaurant part.

And we had a lot to do with the transaction of the musicians every week. I had met a lot of the big musicians in those days. But not that I personally had anything to do.

I was working for somebody.

DAN: Did you know the village at that time?

MIKE: I came into the village, I would say, when I was young, maybe a couple of times.But I came here with some friends because I didn’t know anywhere.

And they always used to give me an impression like you would go to some kind of a... like the Coney Island. That was the second Coney Island, to my knowledge. Somewhere or the other that I didn’t feel at home at all in those days.

And I never made a policy to come down to the Village like on my day off or something. Even though the first few years that I worked, I never had a day off.

HOOKER sings: It’s 19 and 52 baby…

BOB P: Mike Porco worked close to 100 hours a week.

His three kids and his wife didn’t see much of him.

BOB P: What was Mike Porco like as a dad in the ’50s?

BOB SR: It was hard. I don’t remember much as a father, to be honest. Because he left when I was 12.

ANGELO: He abandoned us early, right?

BOB SR: And my mother didn’t care about anything but getting him back. So really, at a certain age, we really didn’t have parents.

ANGELO: We were never hurting for money.

BOB SR: But We never saw him…

ANGELO: He used to pay for the apartment, he used to give us money for food.

BOB SR: We were basically on our own. Uncle Louie was the closest with me, my brother, and my sister.

ANGELO: He looked after us when my father abandoned our mother. He was like our father. We were close, you know.

BOB SR: Once my father left, my mother was a basket case. Mike Porco and Mary Reda, that was her maiden name, were first cousins. That’s how they met.

I think that’s why I’m a little mental. At first I thought it was my sister and my brother, but...

BOB P: The Bastone family owned Club 845 where my grandfather worked as a teenager. Two bartenders from the club, Mike and his cousin Joe Bastone, bought Gerde’s Restaurant in 1952.

Mike ran the day-to-day operations of the space. Joe was a silent partner. Later, in the 1960s and 70s, Bastone and Porco were at the same time partners at Gerde’s and competitors on 161st Street in the Bronx.

Joe owned the Yankee Tavern and Grandpa owned the Stadium Trattoria. The Trattoria held no concerts and had no live music, just Italian food. Mike’s oldest son, my Uncle Angelo, was brought into the partnership deal.

The Yankee Tavern and Stadium Trattoria sat directly across the street from the old Yankee Stadium.

ANGELO: The guy he worked as a bartender with, Joe Bastone at 845, in 1965, they became competitors. Daddy owned the Stadium and the other bartender opened up the Yankee Tavern on 161st Street.

BOB SR: Well, the Yankee Tavern was up further.

ANGELO: No, right across the street.

BOB SR: Wasn’t the Earle Movie across the street?

ANGELO: And that’s where the Yankee Tavern was.

BOB SR: No, the Yankee Tavern was up the block.

ANGELO: No, right on the same block, Bob.

BOB SR: No, but it wasn’t on the corner?

ANGELO: Daddy’s place was here.

ANGELO: Daddy’s place was across the street.

BOB SR: From the Earle Movie, but the Yankee Tavern was here.

ANGELO: Here was the Earle, here was the Yankee Tavern, here was the courthouse.

CHAPTER: THE FIFTH PEG

DAN: Did you know that you were going to open Folk City?

MIKE: No, I couldn’t even dream.

ANGELO: I remember the old Folk City, the old Gerde’s, and I used to work there as a waiter on the weekends when he started the shows. And Izzy Young must have came in and had a be in ’59, because when I got out of the service, it was still Gerde’s and he still had the restaurant.

GEORGE: When I met Mike Porco, he was saying,” oh, you’re Gerde’s, this is your place!” He wanted to know if I was related to William Gerde’s, which I wasn’t, but he said, “I buy this place from William Gerde’s and I keep the name and I don’t lose the customer. “

And, have you talked about the apostrophe?

BOB P: Why is it where it is?

ANGELO: You know, originally, there was a restaurant and he still called it Gerde’s.

They used to close at night and they catered to all the hat; the factories around there. I used to work down in the village. I used to go eat in Gerde’s and my father at that time was put in as a partner.

MIKE: And, we took the place over and we were running under the same routine that he was running before we took over. Four years later, the city decided to take over all that area, nine square blocks. The building was demolished.

We were lucky, in a sense, I call it lucky, I don’t know, maybe it wasn’t, we found a place a block away and the number was exactly the same, 11 West 3rd, we moved to 11 West 4th, just one block over.

DAN: What year was that?

MIKE: This was in 1957.

BOB P: Right around that time, near the shank end of the Village Beat scene, a young man opened a store in the heart of it all. He called it The Folklore Center

IZZY: Well, I used to hang around 4th Avenue when I was a pet for about 20 stores out of the 40 stores and everybody knew me and I knew everybody and they knew I was interested in Folk music and poetry but more in this case, now Folklore.

I opened a store in1957 and I’m thinking I was an idiot to open a store with like 10 shelves of scholarly books on Folk music on MacDougal Street, I’m totally insane!

HAPPY: So I used to come down to Washington Square and met tons of people that are still, some of them are still my friends today which is really the most amazing thing, it was like a great social gathering and I learned tons of songs and then when you opened your store, that was like the Mecca.

I was there at the opening, the opening day, the only reason I know that is because I saw a picture, it was the opening of the Folklore Center, and there I was.

MIKE: Even though we had a brand new place and beautiful place, not too many people were left out of the one we had before. I started to think that we had to do something else on nights, on nights we used to be closed and I said maybe if I get a little help from the night business maybe I do a little better living.

DAN: Was there any music at that time

MIKE I try a piano player, I tried guitar and mandolin.

DAN: Where did you find those musicians?

MIKE: Like I knew maybe one or two of them, they used to come running around I know they were musicians so I knew a couple of them and I asked, would you know someone that would like to work for a couple of hours on nights, have like a dinner music.

IZZY: Like at that time, I knew every single musician in America at that time. People would come just to spend 15, 20 minutes with me. I actually decided who I was going to put on in concerts.

So I was happy then, 20 people came, happy, 30 people came, happy. I was living the life of Riley, I was doing something good and it never occurred to me that I’m not making a living out of it. I can’t believe that people came to my concerts, you can drown in dryness, there’s no water, there’s no beer, there’s no alcohol and they came in with the guitar and they put the case somewhere in the back, you can put the jacket in the toilet or something.

MIKE: So I started with different kind of tries but it looked like it didn’t do too much, not the music but even the night dinners it was not picking up any too much until then a fellow, he had a store in a Village, Izzy Young.

IZZY: I didn’t even know his name was Mike Porco actually. I was getting to be pretty well known in ’59. The people that came to my other concerts, they liked having the idea of having a little drink also.

BOB P: In your book you say that Tom Prendergast convinced you to come over and check out this cabaret over here on 4th and Mercer so was it premeditated?

IZZY: Aren’t I supposed to tell you that? You’re not supposed to tell me that.

Tell me how you start it! who’s interested in what you’re saying?

BOB P: Tell me as much as you remember about coming to 4th and Mercer to Gerde’s restaurant.

IZZY: Tom Prendergast was a guy I never heard of, I didn’t know who he was, he was never was in my store and he was well dressed and he said you know there’s a little place there on Mercer Street and I think it would be a good idea if we make a little club. So me, I trust anybody.

I said okay, so we take a walk here and there’s your grandfather sitting there with his one customer and there’s us and us.

We just walked in.

MIKE: And he saw the place and it was much larger and it was brand new and the place looked beautiful so he approached me and said would you be interested to have a folk music here? I told him we could have a folk music or any kind because we do have a cabaret license here but I don’t know what’s folk music. So in order to make me understand he says,

Did you ever hear of Pete Seeger?

I says yeah. He says you ever hear of Burl Ives?

DAN: Burl Ives?

MIKE: I said yeah, I saw him in a movie he play his guitar and sing and he says well that’s what is folk singing. I said yeah, you would like to try something like that we might get together. And sure enough we got together.

IZZY: We came in and he was sounding tired and bored and nothing was happening which it wasn’t.

And we say, you know we’d like to start a little club here. And he said sure.

ANGELO: Cuz you know Izzy Young came in and he said you want to try this at night and that’s how it started.

IZZY: And We opened up like a week later with no big advertising, no big nothing except the store getting the word out.

AUDIO 2

ANGELO: I used to work there as a waiter on the weekends when he started the shows.

MIKE: We had a called it The Fifth Peg for a while.

IZZY: And the agreement is insanity.

We get the, I forgot, 50 cents or a dollar to cost to go in and he got the drinks. So the place was filled with people drinking and we’re not being filled with money.

BOB P: Uh, was there a written agreement at all or just a handshake?

IZZY: No, no.

Was there a handshake even?

No. It went pretty damn well, but we really couldn’t make any money.

BOB P: You came up with the name for the cabaret?

IZZY: Well, the two of us came up, the Fifth Peg.

And it was a good name. A little dinky.

BOB P: This is your words.

Uh, this is in your book. “Tom and I opened the Fifth Peg on January 8th on 11 West 4th street. Erik Darling donated the name and sang a guest.

IZZY: I forgot that. Okay. So there you go.

I thought it was an odd name because a lot of people don’t even know the name of the Fifth Peg. And then I felt, well, if, if the thing turns out well, people will understand what the Fifth Peg is.

NBC ANNOUNCER: This evening, we’ll take you to Gerde’s, a brand new cabaret here in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village section, devoted exclusively to folk music and folk singers.

CHAPTER: THE BLUES

HAMMOND SONG: TELL THE MAN TO CHECK THIS OIL.

BOB P: In the late 1950s, college campuses in a growing number of cities around the country were experiencing the blues. The southern bluesmen found work playing for growing audiences. And thanks to Izzy Young, the Folklore Center was a place where musicians could go to jam and learn from each other.

IZZY: Listen, I’m talking now, black music was coming up, so I can almost tell you the day that people got interested in black music. People would come just to spend 15 minutes, 20 minutes with me, so I felt very good about it.

BOB P: The next best way to see and hear the Blues would be to see performances at the two Bonafide Blues Clubs in Manhattan.

ARLO: The two places that felt like home were Gerde’s and the Gaslight.

JOHN: The Blues scene in New York was Gerde’s Folk City. I mean, the Gaslight was great, but Gerde’s paved the way.

What was so phenomenal about Gerde’s was that a lot of the great Blues artists, Lightning Hopkins, John Lee Hooker, Roosevelt Sykes, Jesse Lonecat Fuller, Babe Stovall, played at Gerde’s.

ARLO: I was just happy to be in a place where I could actually see them, because my main focus in those days was just seeing exactly what they were doing. I mean, really focused and really paying attention.

Where their fingers were and how they did it, because that’s the stuff I wanted to steal. I knew that I had to watch somebody.

JOHN: Gerde’s Folk City was the place that had everything.

Early rock and roll, early everything. It was happening.

ARLO: You heard what people were doing, but you didn’t know exactly how they were doing it until you actually saw them.

You had to go there, you had to be there, sit there. And that energy of doing that was so exciting that it changed the course of music history worldwide. There’s something pretty cool about being a link in a very long chain.

JOHN: These were amazing guys, great players, just rockin’. But where else could you see Roosevelt Sykes?

BOB P: I was introduced to the Blues differently. When I was 10, the Blues Brothers movie brought John Lee Hooker to my eyes and ears.

My dad told me, that guy used to work at grandpa’s place. I thought, fucking wow!

HOOKER: Howl, howl, howl, howl.

BOB P: For my entire life, I always thought how cool it must have been for my grandfather to have these guys hanging around his bar.

HOOKER: Oh, I feel so good.Well, mama likes to boogie. Mama likes to boogie.

Everybody likes to boogie. I’m gonna boogie.

BOB P: Gerde’s became the premier venue to see the original apostles of American blues.

Everybody was cool with Mike Porco because he was honest and fair. Everybody ate well, they drank for free. Several people even recorded albums there.

When they weren’t working, people like John Sebastian, Bob Dylan, Happy Traum, everybody could learn from the masters in person.

🎥🎥🎥🎥 It has been said that I was SITTING ON this film for a long time and keeping it to myself so now I shall remind you of the ten or fifteen minutes that I have already given away on YouTube and I will share with you here ANOTHER TWENTY FOUR minutes for free because it must act as the best business card imaginable and I will upload the newest version of these 4 chapters MIKE AND GERDE’S, MIKE EARLY LIFE, THE FIFTH PEG and THE BLUES with recently added Ai ANIMATION that will BLOW YOUR MIND to show the potential of making still photos and scripted scenarios come to life. Look at the

There is NO-PAYWALL for the ANGEL FILMS CLIP BELOW. THANK YOU SUBSTACK FOR BEING IDEAL FOR BLOGGING AND STORING LARGE VIDEO. ENJOY> HEAR MY PRAYER that it gets seen by the right person. Perhaps that person is YOU. I don’t have to sell you these 24 minutes I only have to sell you the rest. 🎥🎥🎥🎥🎥🎥🎥🎥

🤌🏼🎙🏆🔮 It is important FOR ALL GREENWICH VILLAGE FOLK REVIVAL enthusiasts to know as much as your average, everyday artificial intelligence internet scouring and music history interpreting essay writer in your phone, tablet or home computer. 🤌🏼🤌🏼🎙🎙🎙🏆🏆🏆🎼🎼🎼👇🏽👇🏽👇🏽👇🏽👇🏽👇🏽👇🏽

Going Public with Positively Porco: Sharing My Film’s Sales Pitch to Attract Partners and Maximize Reach

🎥🎥🎥🎥 HOT OFF THE PRESS 24 minute TORCH video BELOW free for all subscribers